In the weeks since author Alice Munro’s recent death, her daughter Andrea Skinner has come forward with a horrifying account of how she was sexually abused as a child by Gerald Fremlin, her stepfather and Munro’s second husband. Years after the abuse, the daughter finally told her mother what had happened, but received no support. The stepfather then claimed that his stepdaughter was somehow at fault, that it was she who had provoked him. The daughter reported her stepfather’s abuse to the police and he was convicted. The mind-blowing twist to this family tragedy is that Alice Munro decided to stay with her husband. As a result, mother and daughter were permanently estranged.

As reported by Elizabeth A. Harris in the New York Times, Munro offered her daughter the following explanation. “She said that she had been ‘told too late,’” Skinner wrote, that “she loved him too much, and that our misogynistic culture was to blame if I expected her to deny her own needs, sacrifice for her children and make up for the failings of men. She was adamant that whatever had happened was between me and my stepfather. It had nothing to do with her.”

For so many of us—writers and readers—this unfolding story is dumbfounding and crushing. In reassessing Munro’s work, we must now wonder if at least some of her stories were an attempt to resolve what had happened to her own child and her family, her choice to abandon her daughter, confessions concealed as fiction? Unless diaries and letters surface in the future, we may never understand how and why this mother, whose primary duty was to nurture and protect, could remain with a man she knew had abused her daughter. I can imagine that by the time Andrea Skinner told her mother of the abuse, their relationship was already fraught as a result of the daughter’s long-suppressed experience. But even factoring in a famous writer’s desire to avoid public exposure and shame, Munro’s choice is hard to fathom. Meanwhile, Andrea Skinner allowed her mother to live into old age with a reputation unblemished, while her own wounds festered.

As a young woman, I experienced sexual assault. And earlier, there were other brief episodes that will still replay, scenes I’d like to erase from brain storage but cannot.

I was about fifteen, on my way home one afternoon after visiting a friend after school. At that time, I imagined myself as something of a tomboy, though during the academic year I had to wear a girlish uniform—a pleated blue skirt and white shirt. By this time, my body was changing. I had my period and new-ish small tits, and I was not happy about these developments—not at all. Even on warm muggy days (and there are many of these in New York City) I tried to hide in my clothes, but the uniform offered no help. On this afternoon, as I stepped off a city bus, a man walked up to me and put his hands on both tits. Unable to process what was happening, I froze, my mind and body unable to react. A boy about my age pulled the man away and yelled at him. The boy’s shouts rebooted my nervous system. I was able to mumble some words of thanks, but was left with excruciating shame—something about me had provoked this man into action and I had been unable to defend myself.

The following summer, I was walking to a ceramics class on a sweltering July morning, wearing jeans and a striped tee-shirt, one of my well-worn favorites, damp with sweat. A man approached me, a 35mm camera slung around his neck.

“You’re so pretty,” he said. “Would you like to be a model in a photography magazine?”

Sensing bullshit, I looked him over, but his face—masked by a pair of reflective aviator sunglasses— offered few clues. He wore tight jeans and the top buttons of his shirt were open, revealing a tangle of curly chest hair, a rakish look favored by the actors I’d seen in magazines, but repellent to teenagers like me who crushed on skinny hairless boys.

The street vibrated in the heat, busy people walked with purpose to their jobs, mothers pushed strollers, cars and trucks whizzed by, and horns honked, because New Yorkers always think this will make traffic move faster. I wanted get out of the heat and magic myself into the ceramic studio, its location on a shaded side street cool even on a hot day. The man with the hairy chest was blocking my path forward, so I was briefly a captive audience. He told me the name of the magazine he worked for, but I’d never heard of it. I would be paid, he said.

Tell me more, said the mercenary imp in my head. She ran a successful babysitting empire that paid for records and new shoes.

Her twin sister, a wary New Yorker, smelled trouble.

“You wouldn’t have to be—” he began.

Nude was the next word in that sentence. This man wanted me to pose for a porn magazine. I broke away into a run and despite the oppressive heat, I didn’t stop running until I reached the ceramics studio. I went to the bathroom to wash my face. In the mirror over the sink I could see that since I wasn’t wearing a bra, the photographer had seen my nipples through my sweaty tee shirt. My changing body had provoked this man, too. Somehow this was my fault.

These are just two incidents of many, not the worst, and they happened in broad daylight. I share them here to reinforce the fact that you never forget these assaults to your body and personhood.

As the mother of a daughter, the world of predatory men has been my nightmare. Since the launch of the #MeToo movement and the takedown of Harvey Weinstein, not a week goes by without a related story. And now we discover that Alice Munro, a venerated writer, quashed a dark family story, known only to the attendees in an Ontario courtroom and a few others who stayed silent. I feel sorrow for everyone involved, especially a daughter whose life was poisoned as a child.

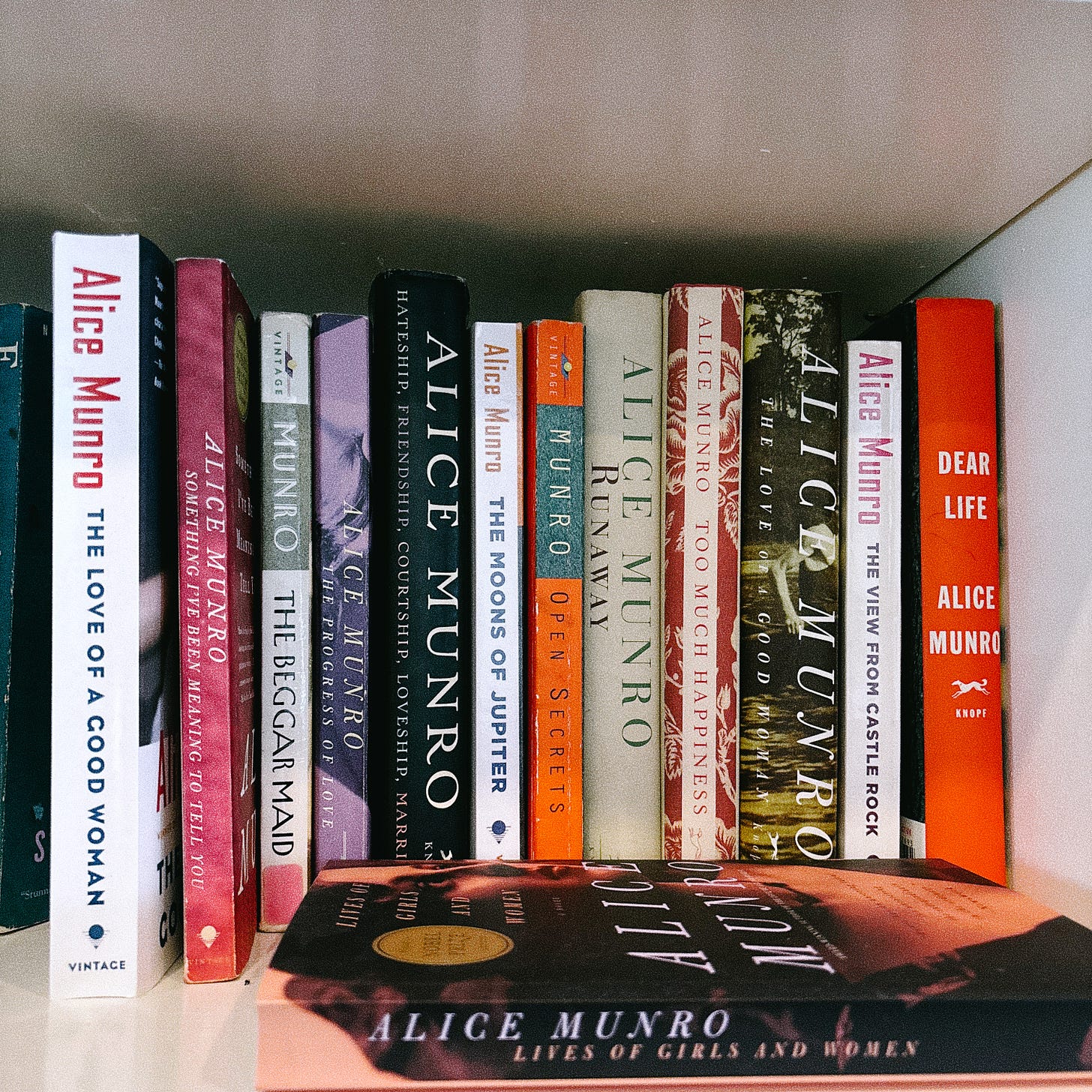

I have read and re-read Alice Munro’s stories because she seemed to be able to inhabit the lives of women who had lived through experiences like this—emotionally and physically abusive parents, sexual aggression, loss, loneliness, heartache. While the world of Alice Munro’s rural Canada was unknown to me, I was always able to see aspects of my own female experience in her stories.

I have re-read one story, looking for answers: “Vandals,” from the collection Open Secrets. The title, a potent theme throughout the book, seems to take on new meaning now. As in many of Munro’s stories, we loop back and forth through time, as events interconnect and echo from past to present. “Vandals” begins with a letter of thanks—never mailed—from an older woman named Bea to a younger woman named Liza. Bea had taken her ailing husband Ladner to the hospital where he died during surgery. She’d asked Liza, who grew up nearby, to check on Ladner’s house. Liza, a frequent visitor as a child, knew where to find the house key and reported that the house had been vandalized in Bea’s absence. In the letter, Bea thanks Liza for letting her know and reminisces about a time, years earlier, when Liza and her younger brother Kenny were little kids living across the road. We learn about Bea’s marriage to Ladner, a loner taxidermist, and how she moved from her own home in town into her second husband’s cabin, set in a marshy forest. We wonder who vandalized the house in the woods. Later in the story, we circle back as adult Liza brings her husband Warren to Ladner and Bea’s house. Once inside, Liza begins trashing the place, sifting through drawers for old papers, smashing windows, painting graffiti on the walls with ketchup.

What is the source of her rage? We move further back in time and discover that Ladner repeatedly raped Liza and Kenny. The abuse is described in the language of a child who doesn’t have words for what is happening and can only find analogy in a machine gone haywire: “When Ladner grabbed Liza and squashed himself against her, she had a sense of danger deep inside him, a mechanical sputtering, as if he would exhaust himself in one jab of light, and nothing would be left of him but black smoke and burnt smells and frazzled wires.”

What a sentence. We see the violence of this man, the pain he inflicts, the blame and shame he transfers to a young girl and her brother. Liza understands even as a child that Bea must know the truth, but has chosen to ignore it. “Bea could spread safety, if she wanted to. Surely she could. All that is needed is for her to turn herself into a different sort of woman, a hard-and-fast, draw-the-line sort, clean-sweeping, energetic, and intolerant. None of that. Not allowed. Be good. The woman who could rescue them—who could make them all, keep them all, good.”

Years after the abuse, Bea offers Liza a piece of costume jewelry and money for college tuition, a way to assuage her guilt. Adult Liza, now married and a Christian, has escaped, but the passage of time isn’t enough to calm her fury. Despite her newfound religion, she releases her pent-up rage on Ladner’s house, an act of reclamation, and a visual representation of the horror she experienced. Does Bea understand that Liza has wreaked her vengeance? The reader is left with unanswered questions, just as we struggle now with Munro’s open secrets.

Thank you for reading and as with all posts here, I’d love to hear from you! More to follow each Friday at noon. I hope you’ll subscribe and share with other readers. You can find out more about my memoirs Perfection and Eva and Eve here and purchase here. I work privately with writers on creative non-fiction projects. If you are interested, you can contact me through my website: juliemetz.com. A first consultation is free of charge.

brave ♥️ ty for sharing

There was an event in the Brooklyn Bridge anchorage years ago and as I recall there was a tree. People were invited to hang a card acknowledging a person who had been raped or sexually assaulted and what the relationship was between the victim and the person filling out the card. The tree was completely covered. Kind of like the most horrifying Christmas tree ever. So many of those cards said My Sister. There was no hearsay. Every writer was an intimate of every victim, which points to how close you are, in any situation, to a victim, whether you know it or not.

It’s just so common and so willfully unacknowledged despite every voice, yours included, trying to wake up a country, an entire world, that is utterly convinced of its own inherent superiority spurred on by pushback from supporters of various powerful people that it’s all a blackmailing hoax. It’s pathological. I feel like the male instinct is very strong; even defining, but it’s used by sociopaths and psychopaths alike to connect to a broad base of males that doesn’t want to see. Plain and simple, doesn’t want to see.