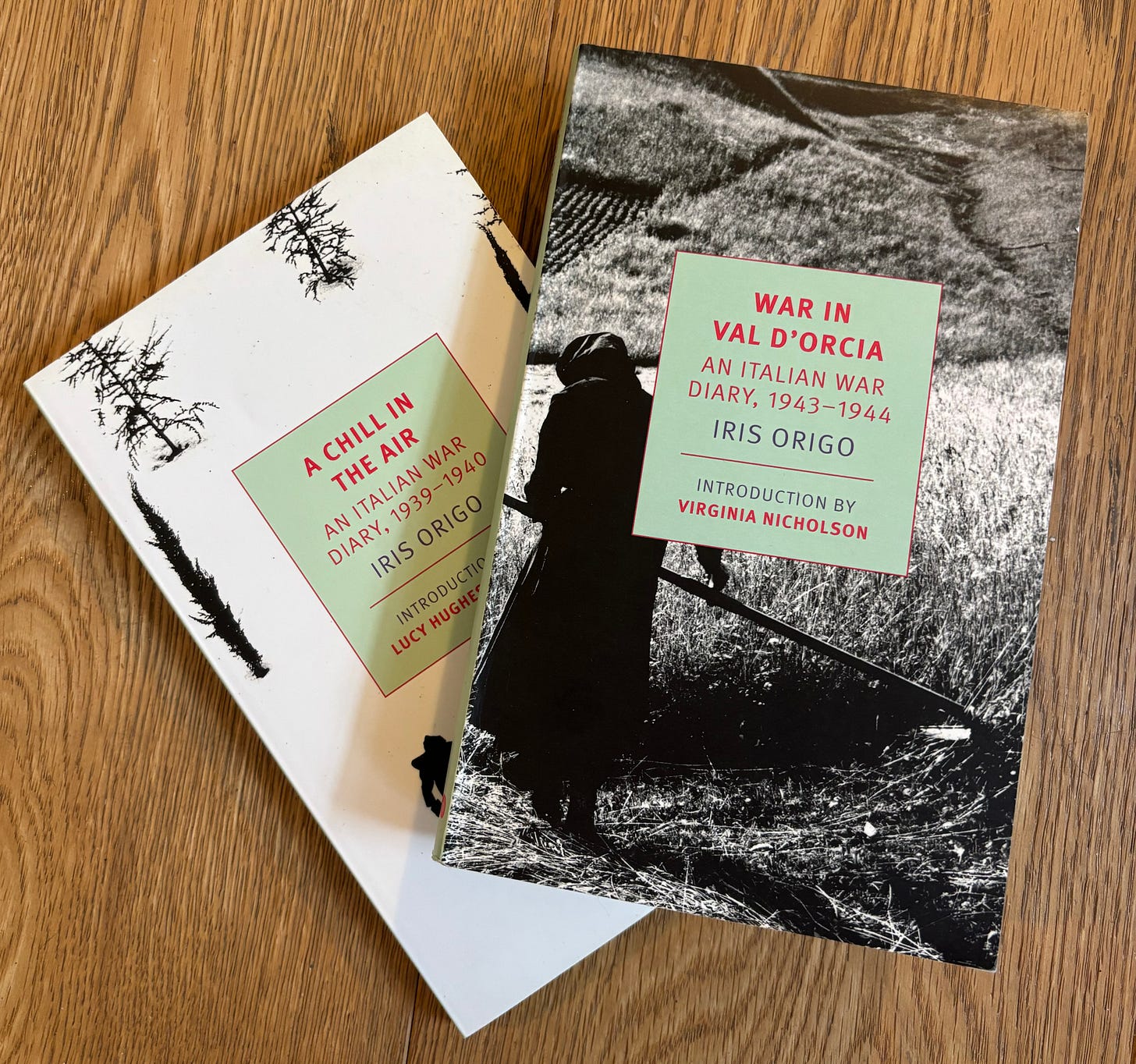

My dad and I often read books together—it’s our mini book club. As an an avid reader of The New York Review of Books, he often chooses from the NYRB backlist, including two diaries by Iris Origo: A Chill in the Air and War in Val d’Orcia. My father is an expert on the history of the second world war, as he served as an infantryman in the Third Army during the Battle of the Bulge. These two diaries offer moving portrayals of life in Italy under Fascism and in this way, they feel all too relevant as we witness our president destroying our government, our liberties, and our relationships with longtime allies, while cozying up to tyrants. Beware leaders who force their citizens to fight and die for false promises of glory and expanded empire.

Iris Origo was born in England but spent most of her life in Italy. Her father, William Cutting Jr., was an American diplomat and her mother, Lady Sybil Marjorie Cuffe, came from a privileged family of British nobility. A charmed life to be sure, until William contracted tuberculosis. Before his death at 29, he requested that his wife relocate to Italy so that Iris would always be an outsider and, he hoped, immune to the nationalism that was so prevalent in Europe. Iris’s mother moved to a villa in Fiesole, joining a community of wealthy ex-patriots. Mussolini and his Fascist party came to power, the nationalism William had feared. Nevertheless, Iris loved Italy. She married a wealthy Italian, Antonio Origo, and they bought La Foce, a property in near ruin in the Val d’Orcia, near the Tuscan hill town of Montepulciano. They would spend their lives rebuilding the estate, several times over.

Clark and I spent some days in this area two springs ago on a guided bicycle tour, taking in the breathtaking scenery now dotted with vineyards and renovated villas, many owned by foreigners. Now, La Foce offers luxury lodging and tours of its elaborate gardens. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, peasants worked the farmland of the estate and lived in small farmhouses. Iris was an outlier as an English woman.

Until I read these books, I had little understanding of the civilian war experience in Italy. In A Chill in the Air, we see how Mussolini draws Italy into alliance with Hitler, bringing the threat of war to the poor and unwilling population in the countryside. The farmers and peasants of the Val d’Orcia survived according to the cycles of the growing season, far from the machinations of politicians in Rome and Berlin. There were many thoroughly indoctrinated followers of Mussolini, but I discovered in these pages that many Italians dreaded the upheaval and hardship a war was sure to bring. On March 28, 1939 she describes her impressions following a speech by Mussolini:

“The applause, however, is definitely less intense than on previous occasions. It is a cold, wet day, and many of the squadristi have slept in tents at the Parioli; but there is also another chill in the air: the universal distaste for Germany as an ally.”

Peasants were conscripted, and hardship began immediately, in no small part because of the disruption to agrarian labor that provided the food supply to more urban areas. For a time, the Axis of Germany and Italy dominated. 1941 brought the United States into the war, but large swaths of Europe were German-occupied. At last, the tide turned with defeats in North Africa.

By 1943, where War in Val d’Orcia begins, life at La Foce has become more difficult, even for wealthy people like Iris and Antonio. The Allies land in Sicily (Operation Mincemeat) and anti-Fascists like the Origos hope that Mussolini would fall from power, paving the way for Italy to arrange surrender terms with the Allies, sparing an exhausted population from life in an active battlefield. Mussolini’s government is toppled, but the new military government fails to arrange terms of surrender. Mussolini stages a revival and a new, if weaker, fascist republic is established. This leads to an agonizing time as the German army retreated northward, wreaking destruction upon its former ally. Jews who had felt some sense of safety in spite of anti-Semitic laws Mussolini implemented in 1938, are now rounded up and deported to concentration camps. The Allies begin a bombing campaign to destroy military and auto factories in Torino and other northern cities. In the south, the retreating Germans and the new fascist government hunt down antifascist partisans who hide in the forests and move constantly to evade capture. Iris endures the pain of childbirth in a hospital in Florence while, in the room next door, a soldier is in agony following an amputation.

During this time, the Origos agree to take in dozens of refugee children from Torino. Iris describes how they and a nurse they’d hired to care for their own children manage to keep life going. Food is scarce, and winter clothing must be sewn and knitted for the children who arrive with only the clothes on their backs. As the Allies continue to push the German army north, a steady stream of Allied POW escapees and anti-fascist partisans arrive at La Foce in need of shelter, food, and medical care. The Allies reach Rome and the threat draws closer. In retreat, the Germans bomb bridges, raid towns and farms for cars, motorcycles, food, and any valuables that have not been hidden in walls or underground. The Origos rely on scarce news from radio broadcasts as well as letters from friends in Rome, but face a predicament we can relate to: what source can they trust? Broadcasts from Britain offer a hopeful picture of Allied progress. Even as they are pushed north of Rome, the German soldiers who eventually arrive at La Foce are convinced that Hitler has a secret weapon that will end the war in their favor. When the Germans take over La Foce, the Origo family flee their home on foot, escorting the refugee children to relative safety in nearby Montepulciano, where they wait out the battle in their valley. War finally ends in Tuscany, and they return to La Foce, prepared to rebuild their home and lives:

“The Fascist and German menaces are retreating. The day will come when at last the boys will return to their ploughs, and the dusty clay-hills of the Val d’Orcia will again ‘blossom like the rose.’ Destruction and death have visited us, but now—there is hope in the air.”

THANK YOU for reading and I’d love to hear from you! More posts on Fridays at noon. I hope you’ll subscribe (paid subscriptions help support independent writing on Substack!) and share with other readers. A free and open press has never been more important, especially as we experience life under an administration in Washington that is no friend to writers or readers. I know you all receive many requests, so to encourage you to consider a paid subscription, I am offering an annual rate of $30. Thank you all for reading and thank you for supporting independent writers!

You can find out more about my memoirs Perfection and Eva and Eve here and purchase here.

I work privately with memoir writers. You can reach out via my website: juliemetz.com.

It feels like we are in the beginning of the cycle of madness but as with everything in the modern era, it will move more quickly. I like to keep in mind that the thousand year Reich lasted barely over 12 years.

My comment might be a bit eerie, but I'll post it anyway, as we are long-standing friends, Julie. My grandfather was Commanding General of the XIV Panzercorps of the German Army in Italy between 1943-45, some 100,000 men, making up about one-third of all German troops in Italy at the time. Although he was clearly an Anti-Nazi and hoped for his own country to lose the war, he certainly was a professional soldier in the best tradition, and did everything he could to hold up the American and other Allied Forces from advancing north. When Italy suddenly left the Axis in September 1943, Hitler ordered to shoot all Italian officers taken captive by the Wehrmacht. My grandfather held about a 1,000 Italian officers in Sardinia at the time, but certainly did not have them shot but organized their quick evacuation and dispersion to the mainland. When retreating to the north - after having successfully held up the Allied Forces for about 6 months at Monte Casino, he made a point that his troops circumvent important cultural cities like Orvieto or Bologna, to safeguard them from Allied bombardment. In his book about WW2 (Frido von Senger und Etterlin, Neither Fear nor Hope, 1960), he describes in much detail how difficult the situation was at the time in Italy to "behave" according to the Geneva Convention. There were the Italian Black Shirts, trying to keep power, there were communist and anarchic partisans, fighting not only the German Army but also Italian fascists and collaborators. Almost a civil war, next to the real one. There were SS-troops next to the German Army which committed horrendous crimes.

What happened is terrible and the main guilt lies with us Germans. There is no excuse, and - as my grandfather wrote - the shame will be on us for at least 100 years. But at least some of us tried to keep it as "shivalrous" a war as possible. (I don't think, there are any Russians trying to do that in Ukraine right now.)